Friday, November 9, 2018 / 1 Kislev 5779

Summary: Rabbi Kosak discusses the conference he attended this past week.

A Common Table

At the end of one of our healing services last week, I mentioned from the bimah (pulpit) that we knew that Pittsburgh would not be the last mass shooting. The next one might not be a synagogue, but it would certainly come. Little did any of us know how little time would elapse before this latest travesty in Thousand Oaks.

But before a dozen people were murdered for doing nothing more than listening to country music at the Borderline Bar and Grill, a congregant approached me after the service. They shared that a rabbi shouldn’t think that there would be another mass shooting—rather, a clergy person should remain optimistic and hopeful.

I sat with that thought, pondering its implications. Then over the past few days at an interfaith gathering, my new and very upbeat friend Juan Carlos stated to our group, “we are not afraid of reality, because we are people of faith.” He succinctly gave language to my own intuition. Put another way, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks once commented that while he is not optimistic about the future, he remains hopeful. Rabbi Sacks wanted to draw a distinction between two types of thinking. The implication is that optimism is based on a realistic assessment of the current situation. Hope, meanwhile, has a larger frame, grounded as it is in faith.

The reality is that whatever conditions lead to gun violence, mass-shootings and hate crimes have not changed since Pittsburgh, or Columbine or now Thousand Oaks. The vast reservoir of guns in circulation, the isolation and anger people carry around with them, insufficient reporting and mental health—none of the many root causes have been addressed. It is therefore sadly rational to assume that our headlines will be darkened again and again. One can’t be optimistic that mass shootings will disappear anytime soon.

Yet we can be hopeful that a better future is ahead. We can be hopeful that love will overtake hate, that unity of purpose can overcome senseless divisiveness, and that people of good will can reclaim our public space. Real hope endures where optimistic reasons are lacking.

With all of that said, I am also optimistic that the necessary conditions for our own society’s redemption have been sown. Across the country, small groups of unlikely individuals are banding together. Experiments in new social institutions that can restore public trust are occurring. Because so many of these efforts are incipient—just beginning—it is understandable that many people are given to despair or are overwhelmed with compassion fatigue. Yet all great changes begin as small seeds. What changes their potential from being signs of hope to indicators of optimism comes down to persistence. What this means is that when there are enough facts on the ground—enough continuing efforts by sufficient people in numerous locations—then societal change begins to crystallize.

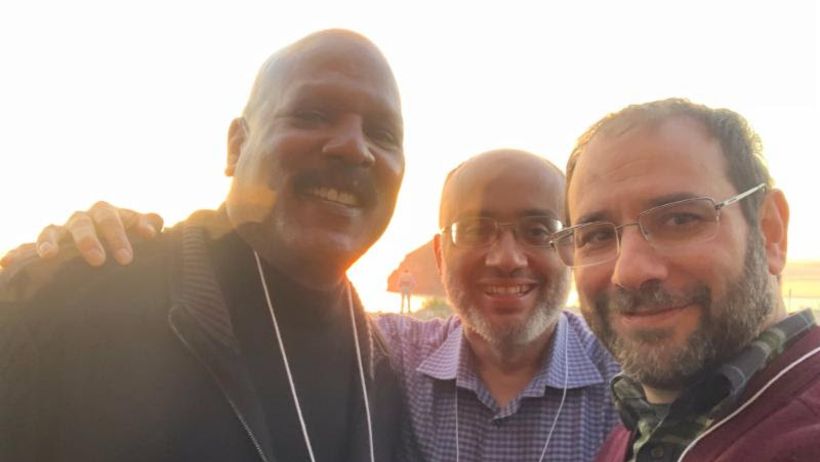

For the past few days, a remarkable group of faith leaders gathered on the shores of the Pacific at our Common Table. Who were we? Muslim, Jewish, Evangelical, LGBT Christians, Buddhist. Catholic, Sikh, Indigenous, Lutheran, Church of Latter Day Saints, Baptist, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Methodist, Church of God, Quaker, Christian Missionary Alliance, Hindu, Baptist, Mennonite, Young Life, United Church of Christ). We were people of color. Native Americans. The marginalized and society’s privileged. People on the Left, the Right and the apolitical. We met in good faith. We struggled with the diversity of our experience. This was not the typical people who attend interfaith gatherings, and still we intend to cast our net further and wider.

At the end of these intense discussions, we each signed a letter of agreement to continue this work. We want to present a unified face of the religious to our state and to our political leaders. We intend to map out the deep support our faith traditions collectively provide to society’s forgotten. We will work together in the spaces we agree, even as we honor where our personal commitments diverge from one another. We pledge to affirm the dignity of all God’s children. And we (for a change) have the material resources to begin this work.

The enemy of this type of work is human impatience, the murky vision we each are granted and the seductive call of violence and hatred. If there really is a pendulum that swings, then the exact place where one might suffer from the least hope and where one can see least clearly, is at the farthest part of the pendulum’s travel. Yet in that darkness is the very promise that a correction is coming.

Whether you want to call that hope or optimism is up to you. But we are setting a place at this Common Table. And I am grateful to have a seat there.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rav D

SHABBAT TABLE TALK

- What common tables are you part of?

- What are you most optimistic about? What worries you the most?

Thanks for voting.

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.