Friday, December 21, 2018 / 13 Tevet 5779

Summary: Rabbi Kosak reflects on some new understandings he has gleaned from the Joseph Story as we conclude the book of Bereishit this Shabbat.

And He Lived

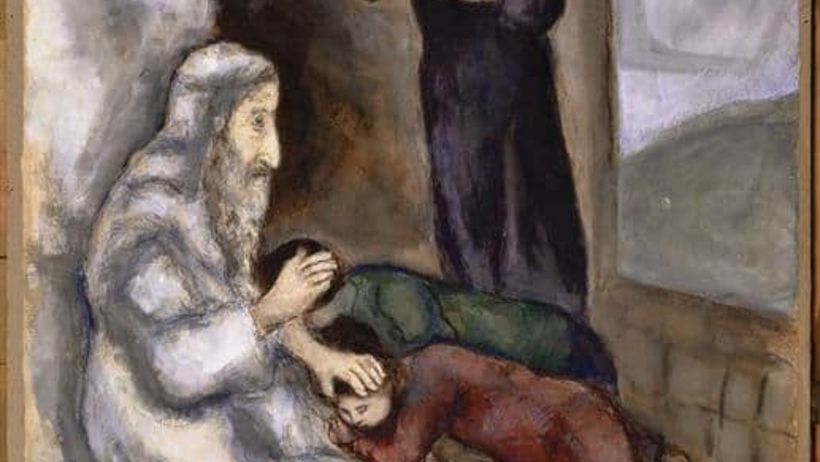

As we conclude the book of Genesis, Jacob and then Jospeh die. Before those shattering deaths, we are presented with a particularly poignant moment. Jacob, now known as Israel, looks at his son, Joseph, and declares with tender vulnerability, “I didn’t dare hope to see your face again, and here God has shown me your children as well.” Here in this scene Jacob will bless Ephraim and Mensahe, as countless parents bless their children every Friday night. An enduring custom is born in the final moments of the patriarch’s life.

But let’s return to Jacob’s simple statement. There’s so much in it. Israel knows he is dying. In this gentle and profound way, he delicately recalls the terrible family trauma in which his children sell their younger sibling as a slave.

He doesn’t belabor what his other sons did to Joseph. He doesn’t unburden himself. Neither Joseph nor we can know whether Jacob carries regret or shame. Does he feel responsible? Does he view all of this as a paternal failure??

Or perhaps Jacob is telling us something different when he lets slip, “I didn’t dare hope to see your face again?” Perhaps this is the earned acceptance of a person of years. Whose life, after all, unfolds exactly as they wish?

We all carry childhood’s expectations into our adults lives, but at some moment, one has to let go of all the things that might have been. This moment, now, is our life. The only cure we have for our imperfect pasts is to live better and fuller in the present—lives suffused with the light that wisdom shines upon our experience. Is that what Jacob is saying?

We might want to know these very intimate familial details about the man who gives his name to our national homeland of Israel. Reality television and social media have accustomed us to uncover other people’s privacy, after all. Still, in its silence, the Torah places limits on what we may know.

It is the Torah’s insistence on modesty even at this moment that has our full attention. Why? Why is the Torah silent when we most want Her to speak to us, when we most desperately need Her guidance in the face of death?

So many people are frightened of death. That’s too bad. For although it is one of our most difficult of teachers, it is also one of our greatest. Knowledge of our mortality forces us to feel. To strive. To seek understanding and purpose. To know that pain is the ultimate cost of love. It forces us awake.

This race of thoughts occupied me recently when my mom took a turn for the worst. Thank God things have improved for her, but not before I took a trip back east and stood in the uncertainty of her hospital bedside. And not before I slept in my childhood bedroom for the first time in decades. And not before I was confronted with the documents of my youth—year books, pictures and college papers. It was one of those rare days when all of time stood before me.

At that point, I was deep in the parshiot of Miketz and Vayigash, when Joseph finally confronts his brothers, and surfaces the family’s long-hidden trauma, weeping while doing so. This year, the meaning of those tears changed. After all, Joseph cries in Miketz as well. It was suddenly so clear that those were the tears of time. Not anger, or regret, or even forgiveness. Joseph sees his brothers and the entirety of his life—his time, his choices, the roads not taken, and all that was and might have been. It’s the weight of time that brought on his weeping.

The fact is that in our daily lives, most of our personal stories are hidden from our own view. We are too busy to see who we truly are. And maybe that’s for the best. We need to stay active, and the past can be paralyzing. Yet every so often, we come completely awake and stand face to face with the fullness of who we are.

In Jacob’s case, this encounter with himself produces an experience of gratitude. “I didn’t dare hope to see your face again, and here God has shown me your children as well.” Even as his death nears, Jacob believes he is receiving more blessings than he could have hoped for. And his natural response to such an abundance is to pass it on as he blesses his grandchildren:

May God bless you and keep you.

May God’s countenance shine upon you with abundant grace.

May God’s face be lifted to yours, and grant you peace.

May we each find our lives a source of blessing.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rav D

SHABBAT TABLE TALK

- Have you had a moment where you were struck by the enormity of your own life? What was it like?

- Ours is not an age of modesty, and so we struggle by the paucity of words Jacob utters to Joseph. What are the advantages of modesty and privacy? Why do you think our age prefers more self-disclosure?

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.