Oasis Songs: Musings from Rav D

Tuesday, July 14, 2017 / 20 Tammuz 5777

Summary: Rabbi Kosak discusses a highly unusual feature in our weekly Torah reading, namely a split letter in the Torah scroll and its implications in our own lives.

A Broken Letter in the Torah

This week’s parashah is Pinchas. The story of Pinchas, and the rabbinic response to his actions, highlight the Jewish capacity to wrestle with morally difficult episodes without yielding to simplistic explanations. The story itself is spread over two week’s readings and is worth a quick recap.

At the end of last week’s sidrah (another Hebrew word for the reading, connected to seder, or order), the Israelites are encamped in front of the Tent of Meeting. There, in the most sacred zone of holy space, which is off-limits to anything profane, something debasing and shocking occurs. A man named Zimri and a Midianite woman engage in an act of coitus in front of the entire community.

For those interested in cross-cultural comparisons, we know that other local religions (including, apparently, the Midianites) practiced cultic prostitution. So there was some precedent or explanation for their behavior. Nonetheless, this flew in the face of our Jewish notions of morality and modesty, as well as being a desecration of our most precious communal space.

We live in a far less modest time, and most of us have seen expressions of adult sexuality in movies.Yet even in our age, it’s hard to imagine how we might respond if we saw lewd acts performed on the bimah on Shabbat or Yom Kippur. Would we watch fixated, frozen in place in our seats? Would there be an outcry? Might we take action and quickly remove the individuals? The truth is that shocking events are traumatic and none of us can be sure how we would react in the moment. We ought to hold that in mind when we consider Pinchas’s response.

Pinchas was outraged, and in his uncontrollable and righteous anger, he took his spear and ran the couple through. For his act of unpremeditated manslaughter, Pinchas is not punished or tried in a court of law. In this week’s reading, he instead receives God’s brit shalom–an eternal covenant of peace that will be passed down to his heirs.

I suspect that most of us make moral evaluations by which we judge actions and therefore the behavior of other people. We hold some behavior beyond the pale and are more forgiving of other human failings. In our own moment, we are even aware of how our politics often determine whether or not we countenance or roundly condemn a given action. Our viewpoint on the magnitude of a crime changes depending on who acted poorly. Yet even in our age of radical relativism, I suspect most Americans would hold that killing two people who were having sex in public is a far worse act than the lewd behavior.

We are not alone in that. Chaza’l, our Sages of old, ruled that if anyone asked whether they could, like Pinchas, take similar vigilante action, the answer would be no. The capacity to ask indicates one has sufficient self-control that it would change an act of righteous manslaughter into premeditated murder. Does their ruling, seemingly at odds with the Torah, indicate a change in cultural norms? A diminution in the importance of sanctity?

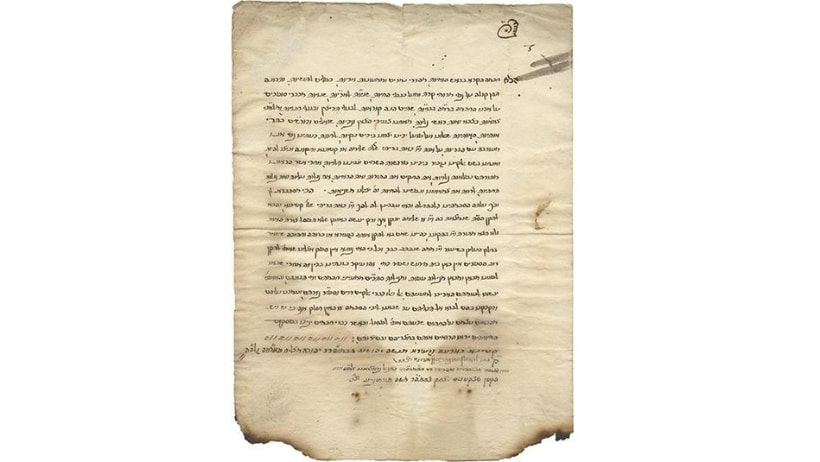

Perhaps not, and here we need to remind ourselves of one of the rules for a Torah scroll. If a Torah scroll has even one letter that is broken in half (ie, if the ink cracked or if the sofer, the ritual scribe, wrote the letter incorrectly) then that Torah is invalid for ritual purposes until the letter is repaired. The sanctity of the Torah depends on the fitness of its entirety. This is why we periodically bring in a sofer to check and, if required, repair the Torah scrolls at Neveh Shalom. It is a costly yet necessary procedure.

Yet every rule has its exception. The word “shalom” שלום in our parashah (see the phrase “briti shalom”– “My covenant of Peace”) is fractured. Specifically, the letter “vav” is intentionally split and is called a “vav keti’a,” a broken vav. What the very writing of the Torah teaches us is that Pinchas’s covenant of peace is a broken peace. It lacks wholeness.

Rabbi Haim Ovadia offers two explanations for this. The first is that occasionally peace must be broken for a higher purpose, such as resisting a dangerous enemy. The second argues that peace achieved through violence will always be incomplete.

In considering these options, what makes the deepest impression is the visual. That fractured “vav” leaves three images on the eye. Two small parts and a third–the letter “vav” that is formed of those two parts and which we still can discern despite its brokenness.

We struggle with uncertainty–and end up mired in paralysis. We rush to judgement as Pinchas does–and destroy something sacred in our haste. There is no alternative. To be human, we must make peace with the fact that we build our lives from the fragments of our imperfection.

So long as we can step back and reflect upon the mosaic of our lives…so long as we can discern the larger pattern…that three part vav of shalom…then God’s covenant of peace will be with us as well.

Next Week’s Topic: Rabbi Kosak will discuss alternative burial options that are ecological and also Jewishly permitted.

Shabbat Table Talk

- When have you felt indecisive recently? What has kept you from making a decision?

- When have you reacted rashly and made a mess of things? What prevented you from reflecting more carefully?

- Do you tend to drag your feet, or are you more like a bull in a china shop? What is your tendency?

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.