Oasis Songs: Musings from Rav D

Friday, January 11, 2019 / 5 Shevat 5779

Summary: Rabbi Kosak looks at some classic sources on the notion of the “chosen people” and explains how Isaiah viewed chosenness as a duty to dispel ignorance and falsehood.

Do you remember that classic line that Tevye utters in Fiddler on the Roof? I know, I know, we are the chosen people. But once in a while can‘t you choose somebody else?”.

Tevye, of course, is bemoaning his hardships, and yet it’s impossible not to laugh. Truth is, many Jews struggle with the concept of chosenness—or even actively dislike it. That’s hardly new. There are ancient midrashic writings in which our sages emphasized that we were the last to be chosen, and that occurred only after other nations turned down the role. So it is fair to say that over the last thousand years, we’ve only reluctantly accepted the title.

That said, the Bible does state, “of all the peoples on earth, Adonai your God chose you to be God’s treasured people,” an “Am segulah.” (Deuteronomy 7:6)

Yet chosenness, when viewed from a Biblical perspective, is primarily about responsibility and purpose and hardly an exclusivist claim. Given that, it would be worthwhile for us to take the concept sincerely and accept the demands it places on us.

What are those demands? Isaiah, speaking in God’s name, powerfully states, “I will also make you a light of nations, that My salvation may reach the ends of the earth.” (Is. 49:6) In other words, if there is a special role for Jews, it is to be instrumental in everyone’s salvation. Remarkably, that understanding rarely required proselytizing. (The 7 Noahide laws, incumbent on every human being, assure everyone salvation)

If we were to accept Isaiah’s mandate seriously, what might it mean to be a light to the nations? How might we accept it without presumption, superiority or an imperialistic mindset?

David Kimchi, or the Radak (1160-1235 CE) comments on Isaiah and notes that the light spoken of is the light of the Torah. By its dissemination, he understood that all of the nations would know peace.

While that’s a tall order, what might it mean in our daily lives?

Isaiah explains: “I the LORD have called you in righteousness, and have taken hold of your hand, and kept you, and set you for a covenant of the people, for a light of the nations; to open the blind eyes, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon, and those that sit in darkness out of the prison-house.” (Isaiah 42:6-7)

The prophet seems to be arguing for two types of action. One is to free prisoners and work for a just justice system. The other type of action is to bring about some sort of enlightenment to people who can’t discern the world in some important way.

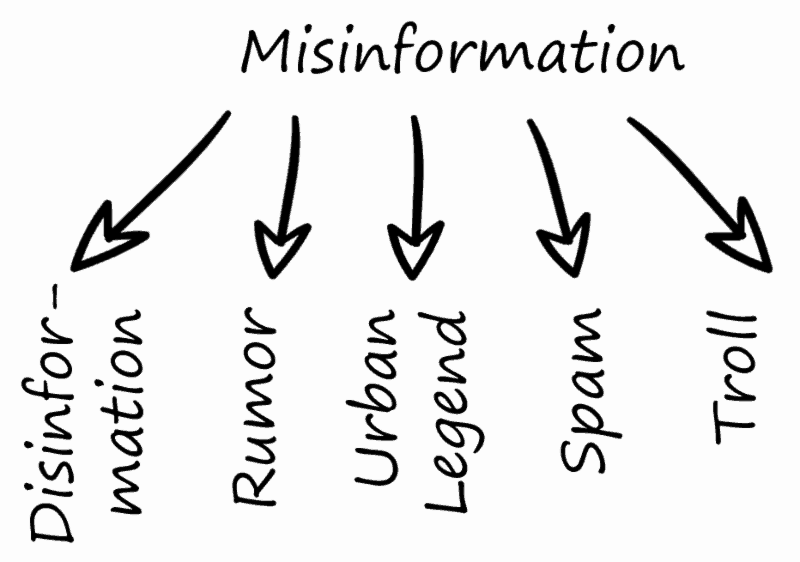

It is the juxtaposition of those two arenas that is worthy of our attention. Closing civil space—reducing the opportunities afforded to all of society—often leads to unjust incarceration. One of the tools used to achieve this end is misinformation, disinformation, or the silo-ing of information. When information isn’t readily available to all, or when people no longer can determine what to believe, societies begin to fragment. Their civil space closes or contracts and human rights usually suffer as a consequence.

While this is a global problem, America has been struggling with these same dynamics over the past dozen or so years, and our social media must share the lion’s share of responsibility. Our social media platforms consistently promulgate false information and fabricated stories. Meanwhile, as we are well aware, people’s newsfeeds are tailored to them and confirm their pre-existent biases. Civility is fraying.

Are there Jewish solutions to this crisis? Are there ways that we are called upon to “open the blind eyes, to bring out those that sit in darkness?” Yes.

This past Shabbat, we held a discussion about misinformation and what we each can do to combat its spread. One suggestion was to call people out when they spread misinformation. Ask them (gently works best) why they believe something and require them to provide a source. Just as we have learned not to turn a blind eye to racist, sexist or anti-semitic comments or “jokes,” so too we can bring that same sensibility to the world of facts and falsehoods.

Ours is a text-based culture. Our entire approach to studying the Torah, Talmud and our legal codes is based on deep rigor (pilpul), substantiation of a claim (tzitut) and knowing where our sources come from (b’shem omro).

While these skills are hardly unique to Jews, they are hard-baked into our identity. We are skeptical, practical and idealistic. This combination has kept us consistently searching for the truth. It means we are primed to do this work.

Robin Shapiro, congregant and faculty librarian at Portland Community College forwarded me a link that can help each of us be more careful consumers of “news” and social media. It might seem like a small thing (or too much trouble) to develop these habits; for Isaiah, however, it was the heart of what it meant to be a chosen people.

The Kotzker rebbe (1787-1859) understood that the real danger of our time in Egypt was not the slavery. It was that we had come to accept our bondage as normal.

Shabbat shalom,

Rav D

Opening Blind Eyes: Four Fact Checking Moves in a World of Lies

- Check for previous work: Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

- Go upstream to the source: Go “upstream” to the source of the claim. Most web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the trustworthiness of the information.

- Read laterally: Read laterally. Once you get to the source of a claim, read what other people say about the source (publication, author, etc.). The truth is in the network.

- Circle back: If you get lost, hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over knowing what you know now. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions.

Sourced from: https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/

Shabbat Table Talk

- What’s the biggest whopper you told in the last month? When did you know you were fibbing, before, during or after?

- How do you deal with misinformation in your daily life?

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.