Oasis Songs: Musings from Rav D

Friday, April 5, 2019 / 29 Adar Sheni 5779

Summary: Rabbi Kosak revisits a recent Oasis Songs article on antisemitism and spends some time thinking about the increasing occurrence of this ancient hatred.

On March 8th in this column, an article appeared entitled, The Question of Anti-Semitisms. It was spurred by the hue and cry against some comments made by Congresswoman Ilhan Omar that many people found to be antisemitic. Simultaneously, many people rushed to defend the congresswoman because they viewed the uproar against to stem intrinsically from Islamophobia or racism because of her skin color.

As I tracked that news cycle, I found myself very disturbed by all the responses I encountered. It was as though antisemitism and Islamophobia couldn’t exist in the same universe of thought, and people had to choose, normally based on their political outlook, how to interpret events. While I have no idea what was in Omar’s heart, or what her intentions were, and while I personally felt no need to either condemn or extol her for those comments, it is manifestly clear to me that both antisemitism and Islamophobia can and do exist simultaneously, and often overlap in interesting ways.

Because none of what I read helped me see things in a new way, the body of that article consisted of a series of questions. They were posed with the hope that our community might produce some novel insights that might push forward our own kehila. Some interesting replies came in that I very much appreciated. Some of those were political in nature; others expressed how remote Israel is to their own thinking. Each had value, and it was impactful to see how many of us are wrestling with this ancient hatred.

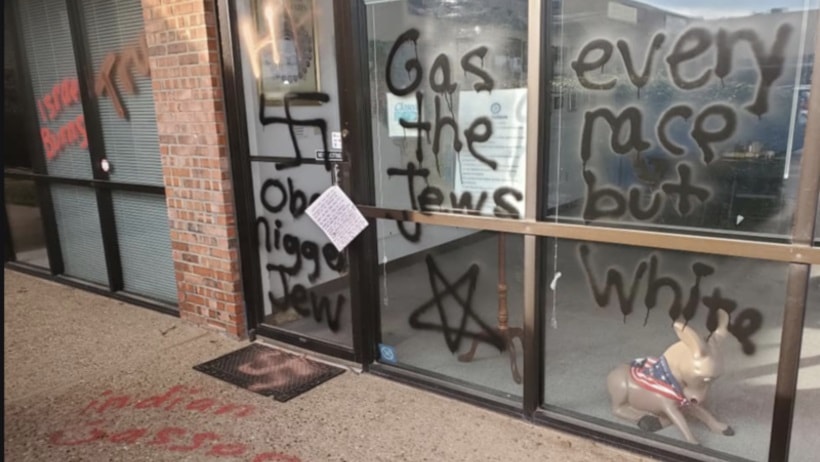

Personally, I am still trying to wrap my head around the apparent resurgence of antisemitism. For those who missed it, a couple of days ago some really virulent graffiti was tagged in three different locations in Norman, Oklahoma: at McKinley Elementary School, the Firehouse Arts Center and the Cleveland County Democratic Party Headquarters. You can find a photo above. It would be tempting to view that as an exceptional incident.

In the world I grew up in—suburban New York—people called me a dirty Jew on a handful of occasions. But then something changed. It seemed as though antisemitism, in America at least, had practically disappeared. It was possible to imagine that here the oldest hatred had been laid to rest. That we had arrived.

I think many of us feel that way. In many ways, it is accurate. That is why when these incidents arise, many of us American Jews view them as aberrations—or as an opinion held only by those with whom we disagree. If I can be quite frank, for a long time I chose to be bored by antisemitism. My boredom relieved me of the responsibility to confront or think much about it. We had more important challenges to confront.

Yet in this morning’s New York Times a cover article discussed the acceleration of this hate. On page A6, the bolded title reads “Anti-Semitism Surges Among Extremes of Right, Left and Islam.” According to the article, French President Emanuel Macron said that in 2018, the incidence of antisemitic incidents was the worst since World War II. These episodes weren’t graffiti, but 500 actual attacks, including the murder of a holocaust survivor in her own home.

Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks spoke to the British House of Lords in September of 2018 in the wake of increased incidents in England. There he stated, “One of the enduring facts of history is that most antisemites do not think of themselves as antisemites. We don’t hate Jews, they said in the Middle Ages, just their religion. We don’t hate Jews, they said in the nineteenth century, just their race. We don’t hate Jews, they say now, just their nation state.

Antisemitism is the hardest of all hatreds to defeat because, like a virus, it mutates, but one thing stays the same. Jews, whether as a religion or a race or as the State of Israel, are made the scapegoat for problems for which all sides are responsible. That is how the road to tragedy begins.

Antisemitism, or any hate, become dangerous when three things happen. First: when it moves from the fringes of politics to a mainstream party and its leadership. Second: when the party sees that its popularity with the general public is not harmed thereby. And three: when those who stand up and protest are vilified and abused for doing so. All three factors exist in Britain now. I never thought I would see this in my lifetime. That is why I cannot stay silent. For it is not only Jews who are at risk. So too is our humanity.”

Rabbi Sacks’ deep insight is how antisemitism morphs to match the central concepts of the age. This makes it an incredibly potent form of hatred, and its power resides in how it connects Jews as enemies of whatever good a society currently values. What is unclear to me is if other groups are subject to the same sort of shifting rationales. Does the basis for hating African Americans, or LGBTQ+ people, or Muslims, or Group X also change to match the current bugaboo? And does it matter if it does, or is hatred hatred always?

Writing in the shadow of World War II, Jean Paul Sartre penned a still-important book entitled “Anti-Semite and Jew.” (The French title is different) I read it during my college years. Sartre proposed that antisemitism becomes a form of faith that frees the stricken person from responsibility for their predicament. At heart, whenever societies face turmoil, as they periodically do, anti-semitism becomes a convenient form of belief. The person who is struggling to adjust to the shifting tides of history can hold firm to their certainty that the Jew is responsible for their plight.

At the end of his book, Sartre turns to the Jew and attempts to answer the difficult question that sociologists and pollsters face—“who is a Jew.” His answer? A Jew is someone who other people—non Jews—point at and say, “they are a Jew.” Certainly, that is a definition that works well for the non-Jew or even the antisemite. Hitler’s Germany held the sole keys to determine who a Jew was.

Yet for the Jew, such an answer can never be sufficient. Our task, in times of relative acceptance, or in eras of increasing hatred, is to form a positive identity. It is to embrace the joy and wisdom of our tradition. If popular culture is correct that “haters are going to hate,” then the only and best response is to live as deeply and fully as we can, to be of service where we can and to muster as much love as we can. All the rest is commentary.

Shabbat shalom,

Rav D

Shabbat Table Talk

- Is all hatred caused by the same thing? If so, what defines hatred?

- Even if there is some common kernel to hatred, will we understand more about it if we distinguish between the many forms of hatred that are expressed?

- It is easy to say that the antidote to hatred is love–but deciding what is love is equally difficult. What do you think is the best response to hatred? What has had the best track record?

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.