Oasis Songs: Musings from Rav D

Friday, December 1, 2017 / 13 Kislev 5778

Rabbi Kosak is in Atlanta this Shabbat for the United Synagogue Convention

Summary: Rabbi Kosak provides a taste of our upcoming scholar in residence weekend. He shares a new book he is reading and offers thoughts about the history and importance of the shabbat table for our well-being.

Scholar in Residence

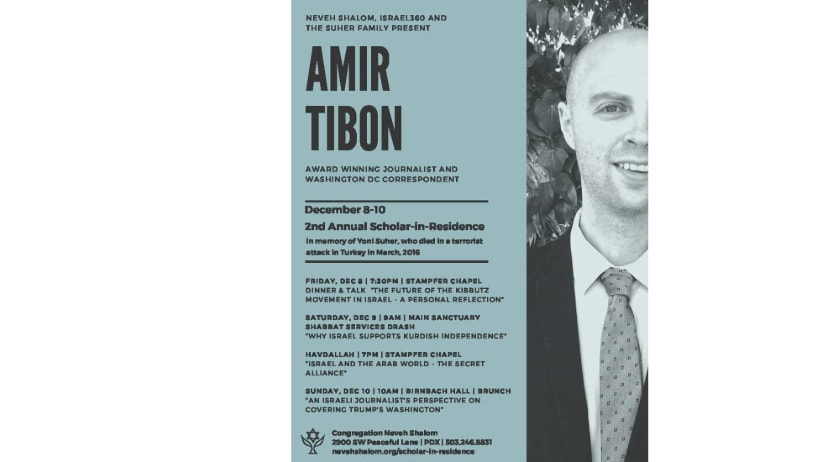

Next weekend our annual Scholar in Residence program returns, when Amir Tibon will visit with us. It is essential for a healthy religious community to bring in outside scholars on occasion. Learning is a key to maintaining our vibrance. We all should express our gratitude to the Suher family for making this possible. It is a fitting tribute and memorial to Yoni Suher, who perished in a terrorist attack in Turkey.

Amir Tibon is a well-regarded journalist and author, and I’ve just started his most recent book, “The Last Palestinian.” It is about the role of Mahmoud Abbas, the current Palestinian leader. Tibon’s long-form pieces have appeared in the Atlantic, the New Yorker and other first-tier publications. Amir Tibon has a fascinating life story that includes a chapter spent living on a kibbutz that borders the Gaza strip. Currently, he serves as the Washington correspondent for Haaretz, Israel’s most literate newspaper. He is a compelling thinker and I hope that you will attend one or more of his presentations. You can visit our website or look at our Wednesday eblast for more details.

Dinner with Edward: Reflections on Shabbat

I’m reading a marvelous book. It’s called Dinner with Edward by Isabel Vincent, and it’s a gift from Marci Atkins. Marci is a member of our wonderful “Wise Aging” group that I am privileged to lead. Privileged, because it is an honor to spend time and learn from these individuals who have so much more hard-won life experience than I. Indeed, it’s not so much that I lead the group as that I convene it.

In any case, while we have a book and topics to discuss, it is the shared stories that get told which make the class a highlight of my week. We all need moments for what our tradition calls “spiritual friendship.” That’s quite a phrase, and rather than define it, it will be better to talk about “Dinner with Edward.”

Edward is the nonagenarian father of the author’s friend. His beloved wife of long decades, Paula, has passed away. Isabel, meanwhile, is going through a rough midlife patch of her own. They form a remarkable and life-affirming friendship, which unfolds primarily over deeply crafted dinners he cooks in his small New York City apartment. Meals always begin with a cocktail. They consist of several courses. They are enjoyed in an unrushed manner. All of that is important. For over those shared evenings, both of their lives are transformed and deepened.

The table, after all, is the civilizing heart of a society. It is the place we learn manners, discover the elevating power of leisure and where appetite is transformed from raw need into an humanizing art. For what sort of people are we if we cannot control our appetites? I learned the externals of that from my parents and came to appreciate the inner dimensions of dinner from my years as a chef.

Judaism, of course, has placed the table front and center ever since the destruction of the second Holy Temple. In Temple days, the sacred rite of meat–taking the life-source of another being–had to occur in a highly ritualized manner. If not for that, we would become inured to violence.

Most Jews understand that the Shabbat table is defined by rituals of its own. We light candles, bless the wine, perhaps wash our hands before breaking bread together. What is less familiar is how each of these rituals and many more are designed to replicate the holy service that occurred within the Temple precincts. In Christianity, the Mass became the sacred meal, but in Judaism, our table is the new altar. The challah is braided so that mathematically, over the course of Shabbat, we can reproduce the 12 “showbread” that graced the Temple altar. It is salted before we eat it because sacrifices also required this.

My family of origin understood this. Most Shabbats there was a white table cloth. The silver candle sticks were burnished to a brilliant shine. We all sat at our places. We politely asked that the serving dishes be passed to us and were expected to take an active role in conversation. Shabbat dinner has always been a taste of “olam haba,” an experience of freedom. One of the great joys in rabbinical school was how we all hosted one another in this maximalist manner that emphasized the power of hospitality. After rabbinical school, the pressures of life made us forget. Let me explain.

One of my failures as a parent is that I have not been very successful at transmitting these experiential values to my children. Most Fridays, I don’t get home before 7:30; to deal with younger appetites, Laura and the boys have already eaten. So as I recite kiddush and motzi, they return to the table for their dessert and sit with me for a while. Fortunately, my boys are polite individuals, but I worry that they won’t possess a profound store of memories of the dining table and family.

A real blessing for my family and me came when Rabbi Posen became our congregation’s assistant rabbi. Once a month, my family can once again all sit down, invite friends over, and practice the ancient art of breaking bread together. Despite my years as a chef in the “hospitality business,” restaurants can’t readily replicate this power of hospitality. There is always a transactional layer to the experience, despite restaurateurs best efforts to disguise that.

We live in an incredibly informal age, and in a time when we are all feeling harried and pressured. Families often believe they can’t create a Shabbat experience. Older couples, free of children, feel “the kids are gone, we don’t need to do this anymore.” So many of us come up with excuses, and I have shared in this guilt. A rabbi and a chef! A former caterer! Shame on me. Yes, we may all be busy, but with a little forethought and organization, no one is too busy to refrain from being a human being. Indeed, if we don’t provide these convivial opportunities for ourselves, we are little more than slaves. It is good to be recovering this spiritual freedom for my family and myself.

The Israeli author, Ehad Ha’am, famously quipped, “more than Israel has kept the Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.” Reading “Dinner with Edward” has been a pointed reminder of that statement. It also highlights my own awareness that wisdom is not knowing what to do, but the willingness to do it.

I always promised myself that I would never be one of those rabbis who preached things that they themselves didn’t do. Walk your talk or don’t talk, Kosak! I guess it’s now okay for me to say, “more than ever, we all need the Sabbath table.”

Hope you have a wonderful meal tonight–or next Friday!

Rav D

Shabbat Table Talk

- If you grew up Jewish, what was your Friday night Shabbat experience like as a child? What was your favorite part?

- What are your current Friday night rituals now? What is the same as childhood and what is different? What caused the changes?

- How often do you allow yourself to have a leisurely meal filled with spirited conversation?

- What was the last great meal you had? Which components made it so memorable?

If you’d like to continue this discussion, follow this link to CNS’s Facebook page to share your own perspectives on the topics raised in this week’s Oasis Songs. Comments will be moderated as necessary.