Oasis Songs: Musings from Rav D

Friday, September 16th, 2016 – 13 Elul, 5776

On Sunday, September 18th, from 1-3 pm, Congregation Neveh Shalom is hosting a remarkable conversation entitled, “Open Book: A Talk Across 3 Generations of Rabbis.” Rabbis Isaak and Stampfer and I met for a trial run through this week. It was fascinating to listen to my elders’ perspectives on many different topics, from changes in Jewish identity to the role of the rabbi.

I hope you will join us. You can find more information here.

What We Do Matters: Nietzsche, the Holocaust Museum and the Jewish View on Life

While in Washington, DC, for a family gathering, two unrelated events collided and provided me with some interesting reflections about how Judaism affirms life. First, I reread most of a novel by the Czech author, Milan Kundera. Then I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. While I have contributed to the museum in the past, this was my first time visiting.

Let’s back up. The novel I was reading is entitled, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” and like many of Kundera’s novels, I first encountered it in college. While I was deeply moved by his books then, I was rather unimpressed with it this time around. Why this is will become clear below.

Kundera begins his story with a reflection on the German philosopher Nietzsche’s idea of eternal return. This unusual concept imagines that everything that happens occurs over and over again, much as they do in the movie “Ground Hog Day.” Because things are infinitely repeated in this theory, our lives and actions gain significance and weight.

Since, however, most of us believe we only go around once, Kundera argues that our lives have an unbearable lightness to them–and that everything we do lacks significance. He even argues that terrible events such as genocide lose their horror because everything is fleeting and without moral consequence.

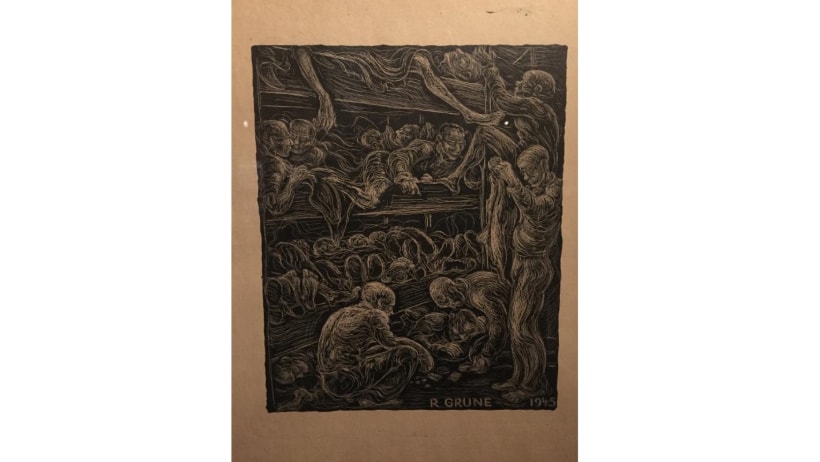

While there are parts of the contemporary world that seem to agree with Kundera’s conclusions, this is hardly a Jewish belief. Indeed, wandering through the Holocaust museum shook me to my core repeatedly, and I could not have predicted what would affect me most. Names of lost settlements that covered the glass walkways pressed down upon me with the sheer and unimaginable loss, but so did the accounts of Jews who took to armed resistance, and the righteous among the nations who, at great personal risk, hid people in farm houses and tunnels.

The worst tragedy to befall my own people would have been pain enough. Yet the magnitude of the Shoah resides in its universal human dimensions. It also seems that some religious traditions minimize human suffering and the existence of evil by appealing to an afterlife. In the face of eternity, our short-lived human pain will appear inconsequential.

Judaism does in fact argue that there is an afterlife, and it has a very rich storehouse of images and concepts to describe that world to come. Yet part of our tradition’s genius is its focus on this world. Suffering matters; our actions matter–even if they only come by once. Even if an eternity follows. That emphasis is why Jews “choose life!” Human existence is consequential (I am not here excluding other life, but focusing on people). The cry of a baby demands we offer comfort, just as a friend’s workplace troubles call for our attentive listening.

Nonetheless, the idea of eternal return is not without merit, though sometimes it actually reduces the significance of what came before. One of the rallying cries of Holocaust activists has been “Never Again!”. Sitting in the final chamber of candles at the museum, my reflections turned maudlin. Terribly, as Rwanda, the gassing of the Kurds by Saddam Hussein and too many other genocidal actions have proven, “Again and Again!” would be a more accurate description of the large scale evil we humans perpetrate. Our readiness to kill others in large numbers because of perceived differences minimizes their moral significance. If we truly valued life, we’d work harder to learn and grow from our past errors. To continue to repeat horrendous actions is a condemnation of life itself. It argues that if existence is frivolous, we might just as well try to grab a bit of power at any cost.

That brings us back to teshuvah, our yearly practice by which we deny such a cynical outlook. We take stock of where we went wrong by harnessing the power of memory and then commit to moving the needle of our lives. We seek a way to live with more compassion and concern and to move through our days with greater awareness. In a strange way, this process reflects the Jewish concept of eternal return. Adin Steinsaltz, one of our time’s greatest scholars, says that through teshuvah, we can reverse time, at least on a spiritual plane. That is, our act of wholesale introspection and behavioral modification rewrites the past.

Ultimately, we decide through our hidden professions of faith whether or not our lives matter. We determine if our short and singular time on this planet has moral significance. When we are cruel to a restaurant server or store clerk or when we fail to give others the benefit of the doubt, we place our faith squarely in Nietzsche’s camp. In fact, it was the shallowness of Kundera’s characters that so disturbed me this go around. They didn’t much seem to believe that their lives mattered, and as a consequence, they mattered less to me as well.

If, however, we try to “fail again a little better,” then our faith is a Jewish one. At one of the sales kiosks on the way out of the museum, I purchased three little tokens–one for me, and one for each of my boys. Upon them are inscribed “What you do matters.”

May we all dedicate ourselves so that we can fill this year with a bit more sweetness.

Blessings,

Rav D

Shabbat Table Talk

You might consider using this article and the following questions as conversation starters over your Shabbat dinner.

- When do you despair that your actions matter? What might you do to realize how much of an impact you can make?

- Some people believe that a particular life lesson keeps appearing in our lives till we master it. For example, if a person repeatedly gets taken advantage of in business deals, that opportunity will appear again until they overcome it. In Ground Hog Day, the main character has to learn how to treat a woman he is interested in respectfully or the day will repeat. Finally, Maimonides seems to believe something similar when he states that true repentance occurs when we end up in the same situation as before but overcome the temptation.

- Do you believe that our life lessons return again and again? Can you think of a personal example when you were confronted with an issue repeatedly?

- History seems filled with examples of human atrocities. Do you believe people can learn to change? Why or why not? If we can change, why does it appear so hard to do so? If you don’t believe we can change, how do you avoid despair?