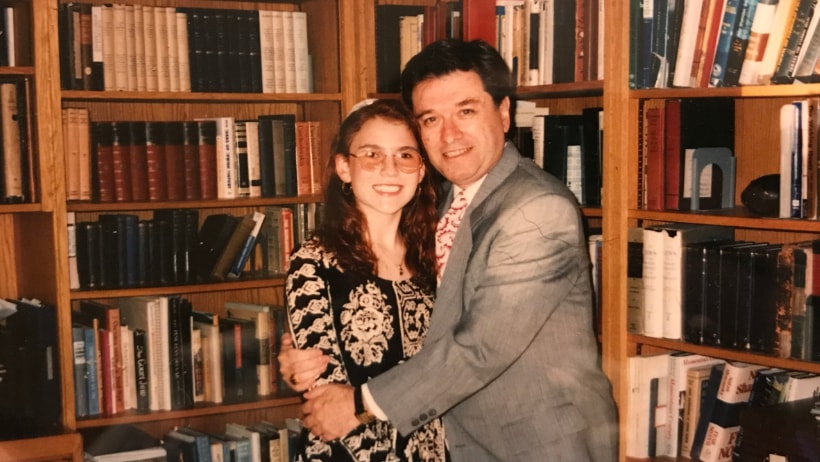

When I was growing up, my grandparents were not just congregants, but friends with our synagogue rabbis. One rabbi, Efry Spectre (z”l), was a particularly close friend. He was practically a part of our family. He was at birthday celebrations and major family simchas, and he was there for our family in times of need. He’d even come over for the Miss America broadcast every year and watch as I paraded around as a contestant. I didn’t know any better about what to expect of a rabbi, so this became my model for the rabbinate. We are family, we support one another, we celebrate together, and nothing makes me more excited than dancing the hora at a simcha with you.

But as much a part of your lives as your rabbi might be, of course there are boundaries to this relationship. Naturally, these boundaries are tested when a life in the public eye also means being intimately connected to others. This lesson is never more apparent than in the laws of this week’s Torah portion, Parshat Emor. Emor focuses on the rules and regulations for the priests, along with the obligations of the Israelites. It covers the observation of certain holidays, including mentions of the holiness of Shabbat, the holidays we celebrate throughout the year, and the ways in which we are to treat one another and animals. The majority of these rituals are meant to be done in public, with the entire community a part of them. To this day, we do not say the Barchu or Mourner’s Kaddish while praying alone because of the strength and power in experiencing these moments with a community.

One clear distinction that the Torah makes is when it comes to what the public figures, the kohanim (priests), can do with grief and loss. They’re put in the tough spot of having to reconcile their personal sorrow with their commitment to serving the people and modeling the acceptance of death as part of God’s plan. As we’re all unique individuals, priests included, grief hits us in a variety of ways, and to grieve in public is no easy task. For this reason, the Torah actually sets some limits.

Chapter 21, verse 1 teaches, “The Lord said to Moses: Speak to the priests, the sons of Aaron and say to them: None shall defile himself for any dead person among his kin, except for the relatives that are closest to him: mother, father, son, daughter, brother or sister.” Traditionally, a priest is unable to be in the presence of a dead body, unless it is a family member, because of this prohibition. This rule stems from the fact that because priestly status is inherited from your family of origin, the rules are waived. In other words, for these most personal and intimate moments, the Torah reminds us that clergy, our spiritual leaders, have an obligation to turn inward and close down to cope with those moments of grief.

As a rabbi, you quickly learn that while the role of steadfast spiritual navigator is important, the best leaders are also relatable because they too are vulnerable. For clergy, the line between public and private can sometimes appear blurred, but the Torah reminds us in Parshat Emor that for both clergy and their congregants, family comes first.